Sweet Tarts, working holiday, and old news are all oxymorons that are fairly universal. For me, doughnut economics is another, perhaps less common, more personal one for me. Who doesn't love doughnuts?! Economics, on the other hand, isn't my forte. I received a C+ in my first economics class in college and since then, it's never brought me that joyful satiation that a chocolate glazed doughnut does. So in what world do these two words come together, and what does the phrase mean?

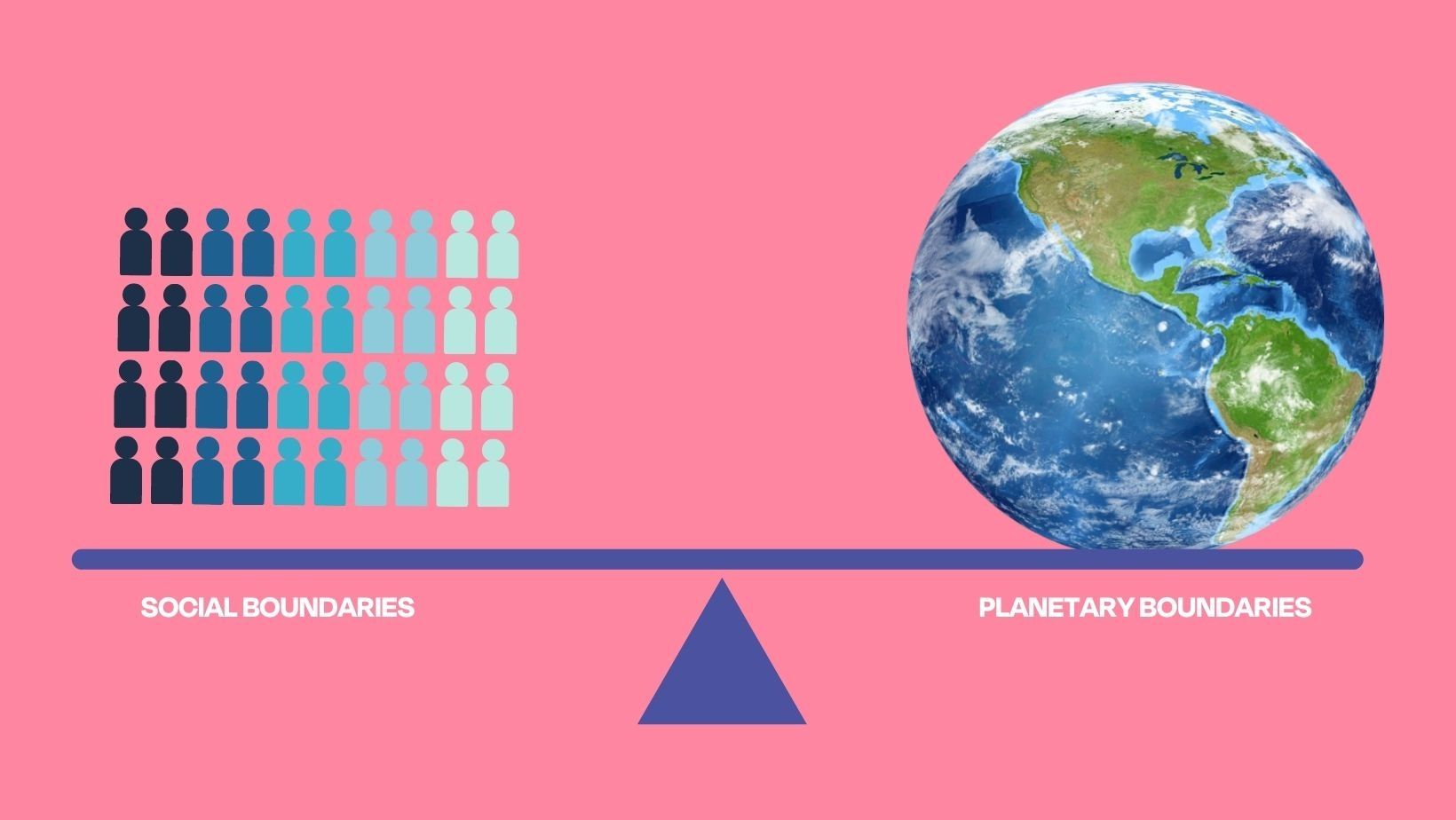

Doughnut Economics is a visual framework that combines the concept of planetary boundaries with social boundaries. The center hole depicts the portion of people that lack access to life's essentials: healthcare, education, and equity. The crust represents the nine ecological ceilings, or planetary boundaries, in which all social foundations are met without overshooting any of the ecological ceilings. If any bleed over the edge of the doughnut, we're in trouble. See below.

The point of this is based on a premise first published by Kate Raworth in a 2012 Oxfam report. According to Kate, 'Humanity's 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet. In other words, to ensure that no one falls short on life's essentials (from food to housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth's life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend - such as stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer.'

To ensure the success of the doughnut, we quantify ecological boundaries using science-based targets. For example, the general consensus for the safe amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is 350 parts per million (ppm), which is the planetary boundary for climate change. We are currently past 400ppm, so we've overshot our limit in this particular category. The social factors are less scientific and more ethically based. The indicator used for food, for example, is the percentage of the global population that is malnourished, and the threshold is appropriately set at zero percent. By setting these boundaries, we are changing the goal from a world of endless GDP growth to a world in which we are thriving within the doughnut.

In modern economics, the free-market is not equipped to solve these social and environmental issues. We've adopted a 'growth at any cost' mentality, casting aside social and environmental considerations as 'external costs' and taking no provisions for them in our economic thinking. This growth at any cost mentality has led to increasingly severe environmental degradation and social inequity, rendering our current state unsustainable. Modern economic theory has fallen short in other ways, too. Adam Smith moved back in with his mother to complete the Wealth of Nations. She cooked, cleaned and did his laundry which allowed him to focus full attention on his manuscript. She didn't even receive a mention in the final publication. To this day, unpaid caregiving is a social necessity which most modern economic theories ignore. If this labor were to be fully valued at market prices, it would represent a large sum without even getting to the 'intangible' social benefits.

With this in mind, businesses can rethink the historical idea of 'growth' and ask themselves three questions:

What core emotional and/or social needs are we helping others to meet through what we are offering?

What are we doing to ensure no environmental harm with how we're producing and selling our goods and services?

What are we doing to ensure we're giving back to the ecosystem we're taking part in?

This type of thinking will help push us closer to a world in which we are living within our planetary and social boundaries. When thinking about the future, we must not only strive for growth, but also for balance.